Facebook, you may have noticed, turned into a rainbow-drenched spectacle following the Supreme Court’s decision Friday that same-sex marriage is a Constitutional right.

By overlaying their profile photos with a rainbow filter, Facebook users began celebrating in a way we haven't seen since March 2013, when 3 million peoplechanged their profile images to a red equals sign—the logo of the Human Rights Campaign—as a way to support marriage equality. This time, Facebook provided a simple way to turn profile photos rainbow-colored. More than one million people changed their profile in the first few hours, according to the Facebook spokesperson William Nevius, and the number continues to grow.

“This is probably a Facebook experiment!” joked MIT network scientist Cesar Hidalgo on Facebook yesterday. “This is one Facebook study I want to be included in!” wrote Stacy Blasiola, a communications Ph.D. candidate at the University of Illinois, when she changed her profile.

These comments raise a serious question: Is Facebook doing research with its “Celebrate Pride” feature? Facebook's data scientists have attracted public scrutiny for conducting experiments on its users: tracking their moods and voting behavior. Much less attention has been given to their ongoing work to better understand collective action and social change online.

In March, the company published a paper that got little outside attention at the time, research that reveals some of the questions Facebook might be asking now. In “The Diffusion of Support in an Online Social Movement,” Bogdan State, a Stanford Ph.D. candidate, and Lada Adamic, a data scientist at Facebook, analyzed the factors that predicted support for marriage equality on Facebook back in March 2013. They looked at what factors contributed to a person changing his or her profile photo to the red equals sign, but the implication of their research is much larger: At stake is our understanding of whether groups of citizens can organize online—and how that collective activity affects larger social movements.

Scholars and activists have debated the effectiveness of profile-image campaigns since at least 2009, when Twitter users turned their profiles green, joined Facebook groups, and changed their location setting to Tehran in support of Iranian protesters. Experts downplayed the importance of such actions; Global Voices Iran editor Fred Petrossian argued that talk of a Twitter revolution "reveals more about Western fantasies for new media than the reality in Iran." Evgeny Morozov, who was a Yahoo fellow at the time, called it “slacktivism,” a “harmless activism” that “wasn't very productive.”

Among other critiques, Morozov voiced two important questions in a larger debate over the value of collective action online. First, he argued that social media solidarity has an unknown effect toward political change, perhaps even siphoning energy away from more effective action. Secondly, Morozov downplayed the cost and risk of that participation. But unlike Westerners showing solidarity for Iranians on Twitter, gender equality in the U.S. involves changes in social relations alongside political changes. Changing one’s profile image in support of marriage equality in America carries immediate risks and costs, from "a quarrel with one’s otherwise-thinking friends – to the life-threatening" as State and Adamic explain in their research.

Indeed, it's hard to look at the compilation of coming out videos posted by YouTube on Friday and dismiss online activity as inconsequential. The “slacktivism” of changing a profile image matters in part because of the personal risks it may entail, and in part because it may contribute to changes in the social acceptance of LGBTQ people. While some might argue a rainbow-colored profile is a lazy way of showing support, it could be an act of great courage for the person changing his or her profile.

What leads people to participate in costly, risky social change, anyway? And might people be more likely to get involved if their friends also participate? That's the question asked by Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam in his research onFreedom Summer, a 1964 civil rights action that placed over 700 college students in black families’ homes in Mississippi to register black voters. Over 10 weeks, there were three murders, “52 serious beatings, 250 arrests, and 13 black churches burned to the ground.” When McAdam found an archive of 1,086 Freedom Summer volunteer application forms, including lists of volunteers' most trusted friends, he had a unique opportunity to test the factors associated with costly, risky social change.

In a statistical model, McAdam found that the greatest predictors of involvement in Freedom Summer were “(a) greater number of organizational affiliations, (b) higher levels of prior civil rights activity, and (c) stronger and more extensive ties to other participants.” In other words, among those who applied and were accepted, people with more participating friends were more likely to go through with their activism, when controlling for other factors. And when Facebook’s researchers studied how support for marriage equality spread on their social network, they cited McAdam’s research and Freedom Summer as an important inspiration.

Although McAdam later studied network structure, The Freedom Summer data couldn’t answer the question of whether seeing others take action prompts a person to get involved. But in March 2013, when millions of Facebook users changed their profile, Facebook’s researchers saw it as a chance to evaluate how participation spreads.

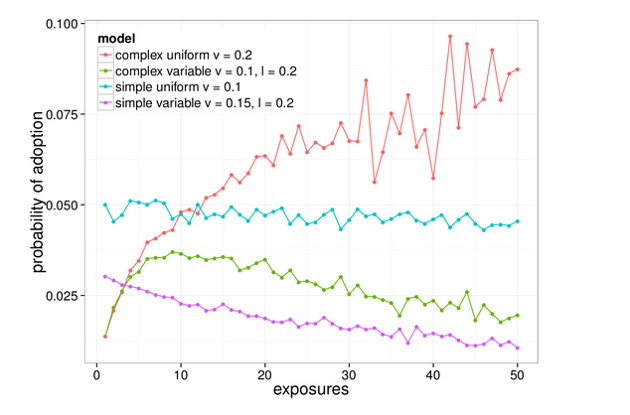

In their study, State and Adamic asked the question: how many times do you need to see a friend change their profile picture before deciding to change your own? They set up two competing hypotheses. The first possibility was that profile changes spread like funny pictures and other online memes, falling off in influence as more people share them. The second possibility they considered was that people need to see others make the change before they follow suit, that “multiple exposures are most effective in determining the adoption of... [costly] behaviors.”

To test these competing hypotheses and develop a new model for how solidarity spreads from person to person, Facebook’s researchers classified profile images from over 3 million users in March 2013, along with 106 million users who were exposed to those changed profiles. Next, they predicted the likelihood of someone changing their profile to an equality image, depending on how many friends they had seen make the change. State and Adamic found that while someone’s likelihood to participate varied based on several factors—a person’s political affiliations, religion, and age, for example—the likelihood to change one’s profile image was greater with more exposures to changes by friends. According to State and Adamic, this likelihood increased “only for the first six exposures.” After the sixth exposure, the relationship “becomes virtually flat.”

But the surprising thing is that profile-image changes don’t seem to move across networks the way, say, a viral cat video might. State and Adamic found a profound difference between how most information spreads on Facebook and the adoption of the marriage equality profile images. While users are quick to share funny pictures and text, the influence of a typical meme on individuals doesn't build over time. But with the marriage equality profile images in March of 2013, users apparently needed “social proof”—they needed to see that others also supported marriage equality—before joining in. As more people changed their profiles, individuals who had seen their friends change their photos were more likely to do the same themselves.

The finding raises a question: Did Facebook users actually influence their friends, or had they selected friends who already shared their views? This is one of the great puzzles of social network research, and it remains unanswered by State and Adamic. Unlike other studies by the company, which test causal claims through experiments, this one merely observed how people behaved on Facebook without the company's intervention. (That's often how social movement research works: data is collected during extraordinary events like Freedom Summer.) Despite their inability to make causal claims, State and Adamic speculate that the millions of changed profile images in March 2013 may have demonstrated to its users, perhaps for the first time, that the majority of Americans already supported gay marriage.

Friday’s Supreme Court decision to uphold marriage equality is another extraordinary event, another opportunity to understand how solidarity spreads in networks. On social media this weekend, many people celebrated the decision. Others spoke against it, or kept silent rather than risk conflict with friends and family. It’s possible that another effect may come into play: a spiral of silencewhere people who now imagine themselves in the minority keep more quiet about their political views. Facebook use has also changed since 2013, as the company’s recent visualization of growth in LGBT Facebook group membership illustrates.

Is Facebook’s Celebrate Pride an experiment on users? Nevius, the Facebook spokesman, told me the feature was designed by two interns at a recent company hackathon. When it became popular with employees, Facebook made it available to all users globally, just in time for the Supreme Court decision and other global pride events. According to Nevius, “it's not an experiment or test—everyone sees the same thing.” That makes it different from Facebook's “I voted” study or its “emotion contagion” research, which tested effects by varying the experience of randomly-chosen users.

Even if Celebrate Pride isn’t a randomized trial, Facebook’s researchers could still retrieve user data in the future to test predictive theories. If changing one’s profile image to celebrate pride is less risky in 2015 after the Supreme Court decision, will the adoption of the rainbow filter have spread more like an interesting photo and less like the solidarity of March 2013? That’s just one hypothesis Facebook's researchers could test.

Furthermore, big changes like new laws and Supreme Court rulings sometimes introduce “exogenous” factors, lightning bolts of causality that allow “natural experiments.” Without changing the Facebook user experience, researchers can still test causal questions with data from before and after the Supreme Court’s decision. For example, Facebook might test if the effect of the Supreme Court ruling on gay couples varies with the number of their friends who shared rainbow profiles. Even with same-sex marriage now legal across the United States, coming out or claiming those rights by getting married will continue to be a socially courageous act. Perhaps couples with fewer visibly-supportive friends would be less likely to get married.

Even seemingly small online actions—clicking the “like” button, changing one’s profile photo—are being tracked and analyzed. Just like McAdam’s research on Freedom Summer shapes our understanding of support for marriage equality, Facebook's past research on marriage equality has helped answer a question we all face when deciding to act politically:

Does the courage to visibly—if virtually—stand up for what a person believes in have an effect on that person’s social network, or is it just cheap, harmless posturing? Perhaps the rainbow colors across Facebook will become part of the answer.

Courtesy: The Atlantic

Blogger Comment

Facebook Comment